Sleuthing Political Relics

A version of this article was published in The Mace, Winter 2025/2026

The University Women’s Club Library. ©️ Laura Hodgson

“Mr Bulteel bets Mr L. Agar Ellis a pony that the present Chancellor of the Exchequer dies a radical”. Brooks’s betting book, 1852

Brooks’s, while no longer politically aligned, is the doyen of political clubs in London. When founded as a gambling house in 1762, it soon became favoured by buff-and-blue-clad Whigs and, by the middle of the 19th Century, 30-40 per cent. of its members were liberal MPs of one complexion or another (Whig, Reformers, Liberals, Liberal Conservatives, and the occasional Radical).

As you enter Brooks’s and head towards the welcoming open fire in the hallway, you will catch your first glance of the club’s genie, the Whig politician and consummate gambler, Charles James Fox (1749–1806). His portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence hangs above the mantelpiece, appropriately framed by 18th-century bone gaming chips. Foxmania continues across the club in the form of busts, oils, pastels, engravings, miniatures and medallions, around two dozen images in all. The club’s betting books are filled with political wagers between members, such as Mr Booth betting Mr Townshend in 1777 that the American War of Independence would be over by Christmas 1779 with America still a colony or Lord Rosebery’s bet with Mr Cadogan of October 1872 that Mr Gladstone would be in office a year hence “barring natural accidents”. The betting books of the traditionally more right-leaning Boodle’s and White’s on the other side of St. James’s Street also contain numerous political bets.

The lavish Renaissance revival Roman palazzo that is The Reform (founded 1836) continues the liberal club tradition, its political mission baked into its architecture as much as its name (which refers to the Great Reform Act of 1832). In the club’s cortile (known as the Saloon), Charles Barry (who went on to build the Palace of Westminster) designed arched niches to display portraits of notable liberals from Charles Pelham Villers to Charles, 2nd Earl Grey and John Bright. The club’s chef, the legendary Alexis Soyer, would support the club’s political and diplomatic endeavours by designing confections such as a two-and-a-half-foot meringue pyramid for the banquet to welcome Egypt’s Ibrahim Pasha in 1846. More recent alterations to the club have been sensitive to its political heritage: the counter of the club’s bar, in what was once its Morning Room, sits on a bookshelf of Hansard reports.

The staircase of the Conservative stronghold that is the Carlton Club (founded 1832) displays a pantheon of party princes, a curious mix of heroes and rogues depending on your point of view. Boris Johnson and David Cameron lurk in the shady “Cads’ Corner” at the foot of the stairs, the ascent of which is rewarded with a shrine to Baroness Thatcher on the first-floor landing. Sadly, John Singer Sargeant’s striking portrait of Arthur Balfour was sold to the National Portrait Gallery to pay for the club’s air conditioning, but a copy can still be enjoyed. There are fascinating Tory relics throughout the club, such as Benjamin Disraeli’s chair and cabinet table and an assortment of Primrose League memorabilia. While dining, you may even encounter the odd piece of cutlery from Arthur’s Club whose former premises the Carlton Club occupies; in contrast to the Carlton, Arthur’s was politically neutral, with visitors to the club’s urinals being offered a choice of standing before a picture of Disraeli or of Gladstone. Poignantly, the Carlton Club also bears the scars of its very own encounter with political violence: in the Morning Room a missing chunk in the stone of the chimneypiece is a reminder of the IRA bombing of 1990. (Political violence is also recorded at Pratt’s in the form of a touching memorial to Lord Frederick Cavendish with the wreath sent by Queen Victoria to Lady Cavendish after the Phoenix Park murders of 1882.)

Similar to The Reform Club, the colossal and magnificent National Liberal Club (founded 1882; building by Alfred Waterhouse, 1884-87) incorporates liberal deities into the fabric of its building. Stained glass portraits of William Gladstone, William Harcourt, Lord Rosebery and John Morley glow over the porters’ lodge. A tall marble statue of Gladstone by Onslow Ford sternly surveys the dining room, with a painting of Harcourt looking across from the overmantel. A cabinet contains Gladstone relics: his axe and bag. Throughout the club there are portraits of other Liberal grandees (with a few Radicals and defectors thrown in): Richard Cobden, Herbert Henry Asquith, Violet Bonham Carter, Inga-Stina Robson, David Steel, as well as the young Winston Churchill before his return to the Conservative Party.

Churchill memorabilia are to clubland what the fragments of the True Cross are to Christianity. Nearly every club, whatever its political allegiance or neutrality, has a portrait or some other relic of Winnie, which is appropriate for a man who is said to have belonged to at least 16 clubs. Perhaps most impressive among these relics are the wooden floorboards at UnHerd Club, salvaged from Churchill’s study in what has now become The OWO hotel and the range at Pratt’s on which Churchill is said to have cooked his dinner after a very late sitting in the Commons. The most stylishly displayed relic is to be found at the Walbrook: Churchill’s hat levitating, more Buddhist than Bulldog.

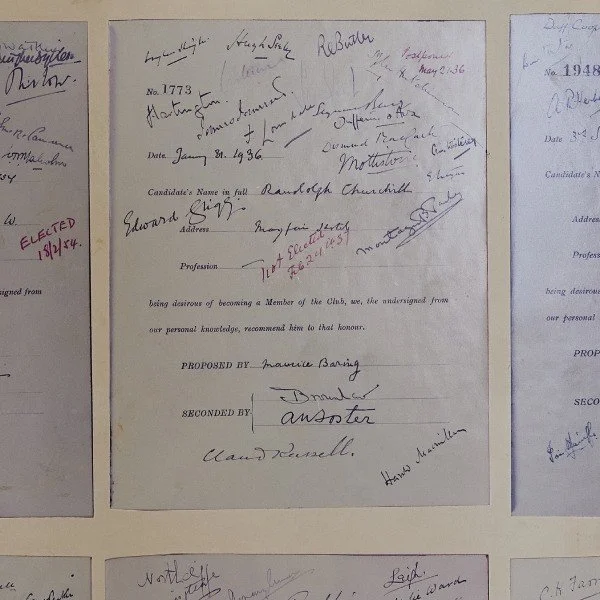

The less political the club, the more surprising a political find can be. At Buck’s Club, Margaret Thatcher and Diane Abbott sit side by side in a pile of political biographies. Buck’s also has its “Buck Flair Suite” smoking terrace - a take on the so-called Tony Blair Suite smoking areas which sprang up across Britain following Blair’s 2007 smoking ban, combined with the spoonerism seen on placards in the 2002 Countryside Alliance protests against his ban on fox hunting. Tucked away on a landing at The Cavalry and Guards Club is the so-called Naughty Boys’ Corner, displaying a portrait of Oliver Cromwell under which hangs his distinctly knobbly stick, as well as a portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II, relegated to this corner of the club by affronted members on the centenary of the First World War. The loos of the Beefsteak Club are papered with extracts from old candidates’ books, displaying the pages of no fewer than 20 politicians including Waldorf Astor, Harold MacMillan, Randolph Churchill and Sir Alfred Duff Cooper.

There are also many non-political clubs whose premises, rather than being purpose-built, were once the homes of politicians. Lord Palmerston lived in what is now the Turf Club. The Savile and The Flyfishers’ occupy the lavishly Francophile house of the politician-æsthete Lord “Loulou” Harcourt; its rococo trompe l’oeil ceilings and gilded white panelling once prompted Max Beerbohm to exclaim: “Ah! Loulou Quinze, I presume?” The Lansdowne is in the house in which Lord Shelburne drew up the Treaty of Independence, while the In & Out occupies Waldorf and Nancy Astor’s home on St. James’s Square. The University Women’s Club is in the liberal politician Lord Russell’s Mayfair mansion and The Caledonian Club was built as the home of Conservative MP Hugh Morrison. You can hedge your bets at the Oriental Club, whose building was home to both a Liberal (Lord Colebrook) and Conservative (17th Earl of Derby) statesman.

Modern clubs wear their politics lightly. The only significant example of a contemporary political artefact I have found is JG Fox’s brilliant caricature at the UnHerd Club, The Political Herds, in which two processions – the Left Wing and the Right – composed of different, contrasting factions (Communists/cancelled, postmodernists/Bullingdon Boys, iconoclasts/podcasters, femcels/incels) wind their ways towards an inevitable clash.

In vain have I searched the Mayfair clubs associated with today’s politicians in the hope of finding a lettuce leaf cornice or tankard shaped toilet. I do worry how well the architecture of clubland will record today’s political generation.

The London Club: Architecture; Interiors; Art by Andrew Jones with photographs by Laura Hodgson (ACC Art Books, £50) is out now.

Winston’s Churchill’s hat at the Walbrook. ©️ Laura Hodgson

Brooks’s staircase. ©️ Laura Hodgson

Randolph Churchill’s candidate page in the Beefsteak Club loos. ©️ Laura Hodgson

Lord Harcourt’s drawing room at the Savile. ©️ Laura Hodgson